Part 1: Introduction – Unraveling the Circle of Fifths

Welcome to this journey into the fascinating world of the circle of fifths, an essential tool for musicians of all levels.

In this first part, we’ll introduce what the circle of fifths is and why it matters in music theory.

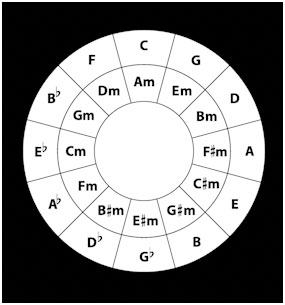

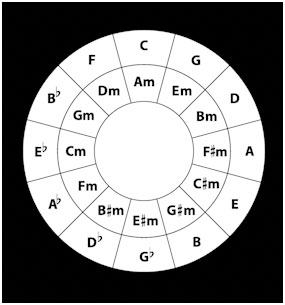

The circle is a visual representation of how keys, chords, and scales are interconnected.

Whether you’re a guitarist, pianist, or composer, understanding the circle will unlock new creative possibilities.

By the end of this course, you’ll know how to use the circle for writing songs, improvising, and even modulating between keys seamlessly.

Let’s get started!

Part 2: Why Is It Called the Circle of Fifths?

The circle of fifths gets its name from the way it organizes keys based on the interval of a fifth.

At the top of the circle, we find the key of C, which contains no sharps or flats. Moving clockwise, each key is a fifth higher.

For example:

- Starting at C, count five notes: C, D, E, F, G. The next key is G.

- From G, count another five notes: G, A, B, C, D. The next key is D.

For guitarists, this is especially intuitive.

Play a power chord rooted on C, then move to the fifth—G.

This simple pattern repeats around the circle.

Each clockwise step adds a sharp to the key signature, and this will be crucial as we move forward.

Part 3: Exploring the Counterclockwise Path – Fourths

While the clockwise direction climbs by fifths, moving counterclockwise steps down in fourths.

For example:

•From C to F is a fourth (C, D, E, F).

•From F to B♭ is another fourth (F, G, A, B♭).

This dual functionality is why the circle is sometimes called the Circle of Fourths.

Guitar players can visualize this easily: moving counterclockwise is akin to descending across strings on a fretboard.

This path becomes particularly useful when exploring harmonic progressions or modulating to keys with flat key signatures.

Remember, flats accumulate counterclockwise, just as sharps accumulate clockwise.

Part 4: Enharmonics equivalents

At the bottom of the circle, we encounter the concept of enharmonic equivalents.

This means that a single pitch can have multiple names, depending on the context. For instance:

•F♯ is the same pitch as G♭.

•D♭ is the same pitch as C♯.

These equivalent notes are critical when discussing the 6:00 position on the circle, where enharmonic keys meet.

For example:

•D♭ major and C♯ major share the same sounds but differ in notation.

•B and C♭ are also enharmonic.

Understanding enharmonics is essential when navigating between sharp and flat keys or arranging music for instruments that favor specific notations, like brass or woodwinds.

Part 5: Sharps and Flats – Adding Layers of Complexity

As you move clockwise from C, each step adds a sharp to the key signature:

•C has no sharps or flats.

•G adds one sharp: F♯.

•D adds another: F♯ and C♯.

Counterclockwise, flats are added:

•F introduces one flat: B♭.

•B♭ adds two flats: B♭ and E♭.

To remember the order of sharps, use the mnemonic “Fast Cars Go Dangerously Around Every Bend” (F, C, G, D, A, E, B).

For flats, reverse it: “BEAD Go Car Fast” (B, E, A, D, G, C, F).

Part 6: Relative Minors – Sadness in the Circle

Directly below each major key in the circle is its relative minor.

These pairs share the same key signature but offer contrasting emotional palettes.

For example:

•C major (bright and uplifting) pairs with A minor (introspective and somber).

•G major pairs with E minor, and so on.

To find the relative minor of any key, count six notes up from the tonic or use this guitar trick: start on a major chord and shift down three frets to find the minor relative.

Let’s consider the key of F:

•F major contains one flat: B♭.

•Its relative minor, D minor, also has one flat: B♭.

Practice switching between these pairs to hear the subtle difference between major and minor tonality.

Part 7: Using the Circle for Chord Progressions

Every major key contains seven diatonic chords.

For C major, these are:

•C (I), Dm (ii), Em (iii), F (IV), G (V), Am (vi), and Bdim (vii°).

The circle visually organizes these relationships.

In C major, the tonic chord (C) is at the top, the IV chord (F) is counterclockwise, and the V chord (G) is clockwise.

Minor chords (ii, iii, vi) sit within the inner circle.

This arrangement simplifies songwriting and improvisation, helping you identify chords that naturally complement each other.

Part 8: Borrowing Chords – Breaking the Rules

Staying within a key is safe, but it can feel restrictive.

By borrowing chords from the parallel minor, you can add emotional depth.

For example:

In G major, the IV chord is C major. Borrowing from G minor, we can replace this with C minor for a more melancholic sound.

Experiment with other borrowed chords like the ♭VII or the ♭III to create unexpected moments in your progressions.

Part 9: Modulating Keys – Changing the Landscape

The circle of fifths helps facilitate key modulation, the act of changing from one key to another.

For smooth transitions, use pivot chords, which belong to both the current key and the new key.

For example:

- To modulate from D major to A major, use D (I in D) as a pivot to A (IV in A).

Keys adjacent to the circle share more chords, making modulation seamless.

The further apart the keys, the trickier the transition—but the more dramatic the effect.

Part 10: Conclusion and Next Steps

Congratulations!

You’ve mastered the essential concepts of the circle of fifths.

From its foundational structure to its practical applications in songwriting, improvisation, and modulation, you now have a powerful tool to enhance your music.

Practice identifying key signatures, creating chord progressions, and experimenting with borrowed chords to solidify your understanding.

Your next steps might include:

•Exploring modes (e.g., Dorian or Mixolydian).

•Writing progressions using advanced modulations.

•Applying the circle to specific genres or instruments.

Thank you for joining me on this journey.

See you in the next course!